- Americans free more than 7,700 forced laborers at Volkswagen plant

- Liberation and occupation completed in two stages in April 1945

- “Volkswagen Jeeps” already produced for US military in May 1945

75 years ago, on April 11, 1945, US troops liberated the Volkswagen plant and the city then known as “Stadt des KdF-Wagens” which was later named Wolfsburg to the south of Mittellandkanal. At the Volkswagen plant, about 7,700 forced laborers were freed. Over the eight weeks that followed, the Americans made groundbreaking decisions for the future of the people, the city and the plant. The brief but marked intermezzo of US military rule laid the foundations for democracy, freedom and reconstruction in the region. In May, the plant was already producing vehicles – Kübelwagen for the U.S. Army, which were then called “Volkswagen Jeeps”. The American occupation ended at the end of June 1945 when the region became part of the British occupation zone.

On April 10, the last 50 Kübelwagen (Type 82) intended for the German army were completed at the Volkswagen plant. Alarms announced the advance of the US tanks into the area. The plant, which had been largely destroyed by air raids in 1944, ended wartime production with a total of 66,285 vehicles.

Liberation and occupation in two stages

On April 11, US troops liberated the plant and the city on the Mittellandkanal. The troops advanced from Fallersleben along the Mittellandkanal to the former bridge at Hesslingen and through the city without encountering any military resistance. On the same day, the Americans advanced towards Salzwedel and the River Elbe. The maps used by the U.S. Army did not even show the city or the plant.

A temporary power vacuum arose in the area. After the SS and the company security force had been withdrawn or had fled before the American advance and the Volkssturm had been dissolved, forced laborers and prisoners of war saw that the end of their suffering had been reached. They were hungry and their pent-up anger at the suffering and injustice they had faced was released. There were some cases of plundering, destruction and violence. To maintain order, the forced laborers formed a provisional security team consisting of French prisoners of war and Dutch students who had been forced to work at the plant. They obtained weapons and vehicles at the plant and used the plant fire station as their headquarters.

Fritz Kuntze, the manager of the power plant, had refused to obey the orders given by the local Nazi leaders to blow up the power plant and bridges. The German-American was determined to prevent damage to the power plant by sabotage as it was essential for energy supplies. Kuntze drove to the US units remaining in Fallersleben with two other engineers, who also spoke good English, and the Catholic priest Father (later Monsignor) Antonius Holling. They convinced the GIs that they should demonstrate a military presence. On April 15, the Americans occupied the plant and the city, disarmed the self-appointed vigilantes and assumed responsibility for administration. The staff officers of the 9th Army gradually arrived up to April 15.

The people

All in all, about 20,000 people were forced to work for the former Volkswagenwerk GmbH, including about 5,000 people from concentration camps. In 1944, two-thirds of the people working at the factory were there against their will, facing racial discrimination. They included Jewish women and men, prisoners of war, and conscripted workers, as well as deported and displaced persons from European countries under German occupation.

On the day of liberation, there were about 9,100 people working at the plant, of whom more than 7,700 were forced laborers from other countries. The largest group, of 3,000 people, came from the Soviet Union, chiefly from Ukraine.

The Americans established Wolfsburg as the collection point for all displaced persons in the rural district of Gifhorn and organized their repatriation. In April and May 1945, the first trains, mainly consisting of open goods cars, left Wolfsburg station for the home countries of the former forced laborers. Some of them faced humiliation and persecution when they returned, as they were often regarded as suspected deserters or collaborators of the Germans.

The city

The US military gave the “Stadt des KdF-Wagens”, as Wolfsburg was then known, its first democratic structures with a Magistrat (municipal administration) and a Stadtverordnetenversammlung (city council). At their first meeting on May 25, the members of the city council decided to rename the city “Wolfsburg”. In doing so, they followed the suggestion made by the municipal administration. The young city took its new, historic name from Wolfsburg Castle, which was mentioned for the first time in documents in 1302.

The plant

At the Volkswagen plant, the American liberators set up a repair shop for their own military vehicles. At the plant and in the surrounding area, they found certain components and stocks and recognized the potential of the plant for vehicle production.

In May 1945, the 9th Army headquarters already reported that the assembly of “Volkswagen Jeeps” had started at the Volkswagen plant with a workforce of 200 people. Initially, the Americans appointed Rudolf Brörmann, formerly inspection manager. as manager of the plant. A total of 133 post-war Kübelwagen utility cars were assembled under extremely precarious conditions to meet the mobility needs of the US troops. These vehicles marked the resumption of production and started the conversion of the armaments plant into a civilian vehicle factory.

This process was continued by the British in June 1945, when they moved into their occupation zone and assumed responsibility for the city and the Volkswagen plant from the Americans. Under conditions which were still challenging, they started civilian series production of the Volkswagen Type 1, the Beetle, just after Christmas 1945.

The liberation – eyewitnesses remember

Sara Frenkel-Bass (born in 1922, living in Antwerp), disguised as a Catholic nurse, the Jewish woman from Poland worked in the hospital of the workers’ camp from March 1943 to April 1945.

“You have no roots. You look for what you have lost but it will never come back. It has all gone.

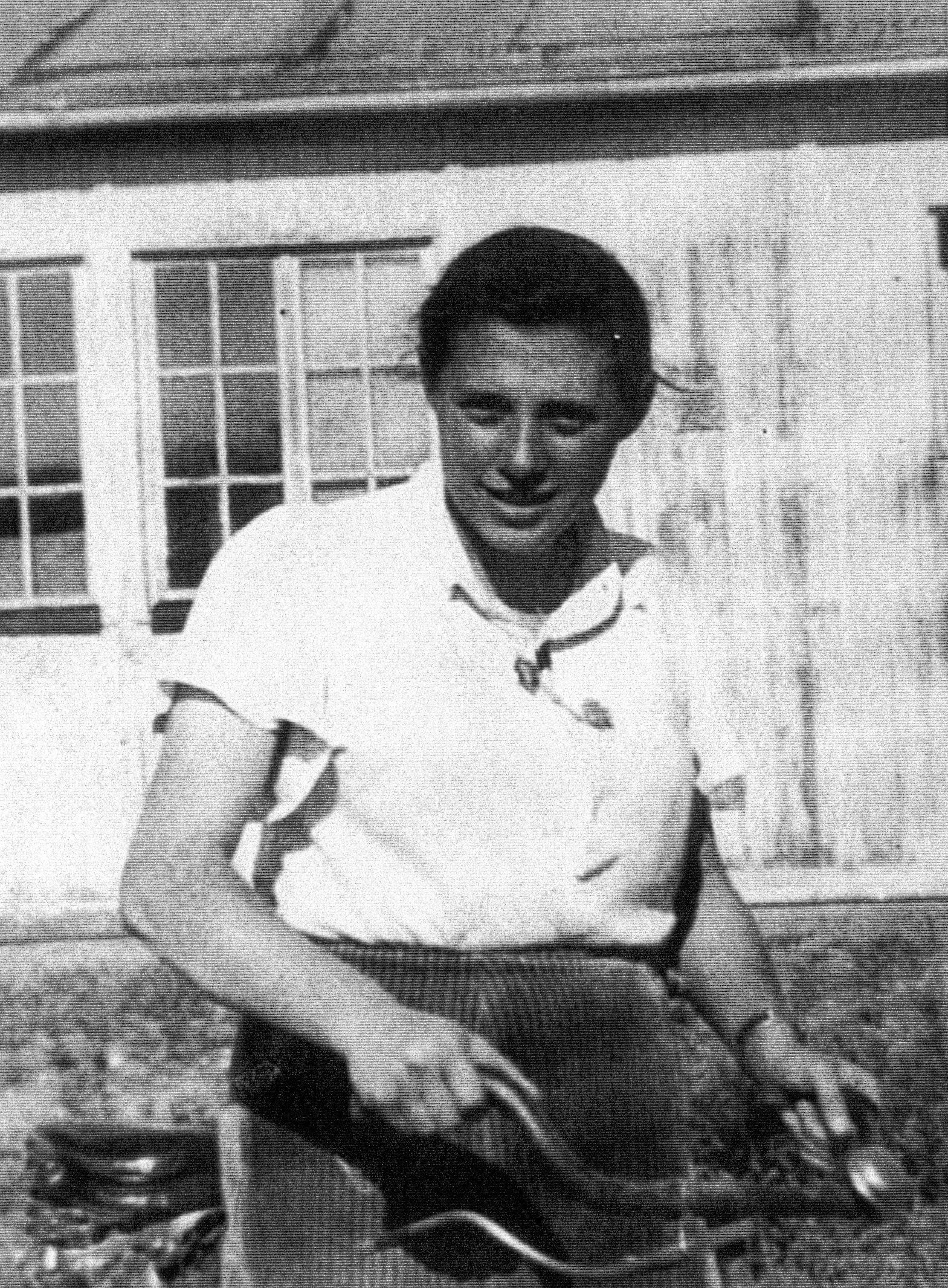

Henk ‘t Hoen (1922 – 2006), the Dutch student was a forced laborer at the Volkswagen plant from May 1943 to April 1945:

“When the first American troops arrived via the neighboring town of Fallersleben, we students immediately established contact with them. Together with some former French prisoners of war, the students had set up a provisional security group to calm down the escalating situation. This group had obtained weapons and vehicles at the plant and used the fire station as its headquarters. As the American troops advanced […] directly from Fallersleben to the river Elbe and at first simply ignored the “Stadt des KdF-Wagens”, our group had to bridge the time until the occupation forces arrived. With some persuasion, we finally succeeded in having a few American tanks drive through the city. Our group preceded the tanks in a Kübelwagen in an attempt to enforce the curfew that had been imposed. Shortly afterwards, the military government established a city commander’s office and we were ordered to hand in all our weapons. The security group was then dissolved. Some of the students who had established the first contacts with the American troops disappeared shortly afterwards, heading back to the Netherlands at their own initiative. The official transports came later.”

Jean Baudet (born in 1922, living in Nice), French forced laborer from July 1943 to April 1945, experienced the liberation in Neindorf:

“Sunday, April 8 – The front is coming nearer. One rumor follows another. Smoke rising at Gifhorn. Presumably sabotage on the oil pumps. Battles in the air. Masses of trucks, cars and soldiers on bikes on the road. My Tyrolean backpack is ready. Only the clothes I need but tinned meat, milk, fat, sugar, a few biscuits. Whatever happens, I want to be ready to head home before, during or after the fighting.

10. April – Sunny weather. Artillery fire the whole day. All the Germans are drunk. Columns of soldiers without weapons and wounded pass by. Complete chaos. When will it all be over?

April 10 – evening: artillery fire nearby. Impressive. Bombs fall on Brunswick throughout the night. Troops are always moving past.

April 11 – 9.00: American bombers over the treetops. People say that KdF has been occupied. They’ve already advanced up to Barnstorf. That’s behind the forest. We pack our things, singing as we do so. Machine-gun fire can be heard. They must be here any time now. The grenades are coming closer and closer.

April 11 – afternoon: Complete silence. Sunny weather. Peace has returned. Only a few severe explosions from time to time. The highway bridges are being blown up. At 2 p.m., farmers give us bacon soup and a piece of bread. We don’t understand what has come over them. At 3 p.m., there is a major alarm. We have to evacuate. So “off to battle”. I decide to hide in the bushes with Georges Chauvineau but we are worried about gunfire in the forest. 3:30 p.m. contradictory order. Everybody is happy: we stay where we are. We immediately get out our cigarettes and football. The evening and night are peaceful.

12. April – The sky is overcast. All quiet. Is the war over? Where are they? What are they doing? 12 noon. 5-minute alarm, fighting on all sides again. We are surrounded. Artillery, bombs, anti-tank grenades, machine guns, all at once. They are coming!

2 p.m. the farmers come back, bringing us sacks of potatoes. I’ve seen everything now! 3 p.m. They’re here. They’re here!”

Note for journalists:

This text and images are available at www.volkswagen-newsroom.com and eyewitness reports of former forced laborers can be downloaded here. Further information on the history of Volkswagen is given in the Volkswagen chronicle, which is available as a multimedia online edition or as a download.

Media

Media contact